A disease is spreading across London, there have been 1000s of deaths which has led to widespread fear and panic. Doctors are not familiar with the symptoms and are trying desperately to try and get an understanding of how this disease is spread while racing to find a cure.

Reading this you may be forgiven for thinking that it was taken from a recent news report describing the outbreak of Covid-19, however, this is talking about another outbreak that gripped the city between 1831 and 1866. That disease was Cholera and is significant for water engineers as it is considered the birth of the modern drainage system.

Now I know this is supposed to be a blog post about SuDS but stick with me we are going to get there.

So, what happened back in 1831

At the start of the 1800’s the industrial revolution was well underway, and London had become the largest city in the world. The population was growing and while this was good for the economy London had a big problem, the city was drowning in its own waste.

At the time the main method of disposal was through night soil men who collected the waste from local cesspits and disposed of it into the city’s old rivers like the Fleet, Tyburn, and eventually the Thames. The problem with this approach was that these same rivers were also being used by residents to wash as well as the main source of their drinking water.

It will come as no surprise that disease was rampant and the first outbreak of Cholera was in 1831 which was shortly followed by influenza and typhoid epidemics in 1837 and 1838. At this point it was widely believed that these outbreaks were a result of poor air also known as the ‘miasma theory’ and it wasn’t until 1849 when a physician called John Snow (who did know something) found that cholera was not transmitted by bad air but by a water-borne infection.

Oddly, the way he discovered this was through an early track and trace system where he managed to pinpoint the cause of a local outbreak to a water pump on Broad Street. Once the handle was removed the outbreak ceased and as a result, the link between digesting contaminated water and Cholera was established.

Figure 1: John Snows Cholera map

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/mar/15/john-snow-cholera-map

Based on this new information and following the ‘great stink’, parliament commissioned one of the greatest engineering projects of the century…the construction of a new sewer network for London.

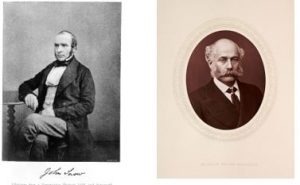

The Chief Engineer on the project was Joseph Bazalgette and his dedication to the project was amazing, he reviewed 137 proposals, inspected every plan, and personally visited every interchange on the project to ensure quality and that there will no leakages. He also insisted that the sewers were constructed using an egg-shape which allowed the system to cope with increasing volumes of sewage as well as speeding up flows to reduce the risk of blockages. The sewers were officially opened in 1865 after which there were no significant outbreaks of cholera.

Figure 2: John Snow (Left) and Joseph Bazalgette (right)

Source: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/cholera-victorian-london

OK, so that is interesting but what has this got to do with SuDS?

We are now on Week 5 of our deep dive into the world of sustainable urban drainage. So far we have looked at how SuDS can attenuate the flow of water as well providing benefits such as improving water quality and promoting biodiversity, however, it is their contribution to creating amenity space where I think they can shine with relation to our fight against COVID.

Now, I’m not suggesting that SuDS are going to have the same effect on COVID as Bazalgette’s sewer had on Cholera, however, they could certainly play their part.

The main thing that me and my family missed during lockdown was the ability to be able to interact with other people. This was especially true of my daughter and there was a huge sigh of relief in the Gennard household when nurseries and parks finally reopened.

Although we are now starting to see restrictions begin to ease, social distancing is still in place, and to get together we are still very much having to stay apart. This raises the question… how are our public spaces going to have to adapt to meet this new norm?

How could SuDS play their part?

We have all seen on the news how schools are adjusting to getting pupils back in the classroom. Some have opted for phased timetables, others marquees while some are remodelling internal layouts to try and get extra classrooms… but what if we could take our teaching outside? We discussed in the green roof post how their inclusion could be used to create outdoor learning spaces, however, we can also use SuDS on the ground. The SuDS for Schools project and the ‘Reimagining rainwater in schools’ document produced by the Mayor of London, highlights how things such as wetlands, Bioretention areas and swales can all be used to create some great outdoor learning environments.

Figure 3: Children at Hollickwood Primary School gardening at SuDS for schools project

Source: https://environmentagency.blog.gov.uk/2015/11/27/suds-for-schools/

Another area that has been greatly discussed during COVID is the benefit of cycling with many cities introducing one-way systems or reconfiguring roads to make extra cycle lanes. SuDS can not only be used to improve the cyclers experience by creating a more appealing place but depending on the chosen feature can also help improve safety. For example, where there is a little more space a linear rain garden system or swale adjacent to the carriageway could provide a physical separation between cyclists and vehicle users.

Where space is a little more restricted, pocket Bioretention areas could be used, similar to the Embleton Road Scheme in Bristol, to reduce traffic speeds in the carriageway as well as again enhancing the area.

Figure 4: Example of linear raingarden in Seattle (left) and pocket bioretention area in Bristol (right)

Finally, something else that has been making the news is that many of our city’s residents have struggled to access green space during the outbreak. This, when combined with the glorious weather we experienced during the lockdown, has been challenging, particularly for those with young families.

The pocket park initiative has been going for some time now and one great example is the Derbyshire Street Pocket Park in London. Here a new community space has been created which includes the following six SuDS components as part of the layout:

- Attenuating Planters

- Permeable Paving

- Small scale green roofs

- Raingardens

- Engineered Tree Pits

- Swale

The project not only enabled all surface water generated from the east end of Derbyshire Street to be dealt with on-site and thus disconnecting this area from the combined sewer system but also created a fabulous community space and generally improved the overall look of the area.

Figure 5: Before and after photos of the Derbyshire Street Pocket Park Project.

Source: https://www.susdrain.org/case-studies/case_studies/derbyshire_street_pocket_park_london.html

Summary

Sometimes we can learn a lot from the past. I don’t know what Bazalgette would think of SuDS systems however, as an engineer I believe he would certainly see the benefit in creating better public spaces and how improving water quality is still a major factor in preventing disease.